Editor’s Note:

This is the second in a series of articles that traces the origin, collection, transmission and translation of the Bible. Each representative article examines one of the four questions pertaining to the inspiration, canonization, textual transmission and translation of the Bible.

The issue of translation of the Bible stems as a natural corollary once the question of the textual transmission is settled. To assess the fidelity and accuracy of the Bible today compared to the original texts we must investigate the issues of translation theory and the history of the English Bible. The task of translating the Bible from its source languages (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek) into a receptor language (English) involves many issues related to the nature of language and communication.

The issue of translation of the Bible stems as a natural corollary once the question of the textual transmission is settled. To assess the fidelity and accuracy of the Bible today compared to the original texts we must investigate the issues of translation theory and the history of the English Bible. The task of translating the Bible from its source languages (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek) into a receptor language (English) involves many issues related to the nature of language and communication.

Is word meaning found in some fixed form of inherent meaning, or is meaning determined by contextual usage? Is meaning located in the formal features of the original grammar, or in the function of words within the grammar? These are just a few of the questions pertaining to translation theory. Some translators maintain that accurate translation requires a word-for-word approach of formal equivalence (KJV, NKJV, NASB, ESV). Others contend that a straightforward one-to-one correlation between two languages actually distorts meaning. These translators employ a phrase-for-phrase approach of dynamic or functional equivalence (NRSV, NIV, CEV, NLT, TNIV). In light of linguistic, exegetical, and stylistic considerations translations produced in accord with dynamic or functional equivalency more effectively reflect the meaning of the original languages. The goal of all translators, no matter what translation theory they may employ, unanimously continues to be the production of an English version that is an accurate rendering of the text written in such a way that the Bible retains its literary beauty, its theological grandeur, and most importantly its message.

The history of the English Bible satisfactorily demonstrates that the Bible of today does indeed faithfully represent the Scriptures in their original languages. For centuries the only Bible available to Western people was the Latin Vulgate composed by Jerome who was commissioned by Pope Damasus toward the end of the fourth century. The Latin Vulgate served as the official version of the Bible throughout Medieval Europe and was restricted to the clergy, monastic orders, and scholars.

The history of the English Bible satisfactorily demonstrates that the Bible of today does indeed faithfully represent the Scriptures in their original languages. For centuries the only Bible available to Western people was the Latin Vulgate composed by Jerome who was commissioned by Pope Damasus toward the end of the fourth century. The Latin Vulgate served as the official version of the Bible throughout Medieval Europe and was restricted to the clergy, monastic orders, and scholars.

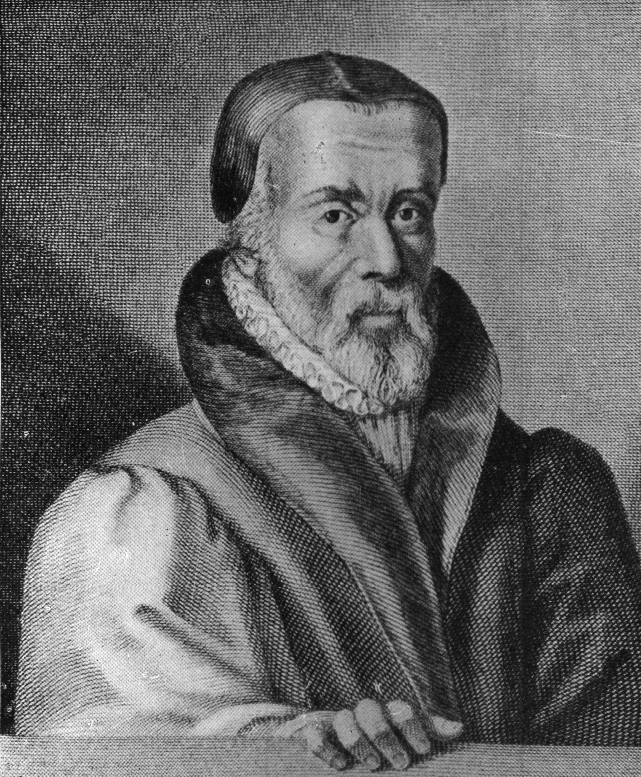

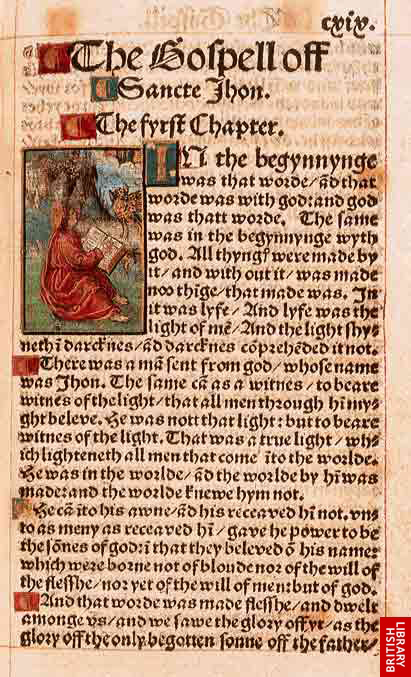

A British priest and Oxford scholar, John Wycliffe (1330–1384), was the first person to make the entire Bible accessible to the common English speaking people. His translation, however, was based on the Vulgate and not on the Hebrew and Greek. William Tyndale published the first English New Testament based on the Greek text in 1526. Two close associates of Tyndale (Miles Coverdale and John Rogers) finished his work by publishing their own respective translations of the entire bible: the Coverdale Bible (1535) and the Matthew’s Bible (1537).

The Geneva Bible of 1560 provided a translation of the Bible entirely from the original languages. This paved the way for King James I to issue a translation that would correct the partisan nature of the Geneva Bible. Thus in 1611, the much celebrated Authorized Version (KJV) largely based on Tyndale’s work, quickly became the unrivaled English translation for 270 years. The twentieth century has given rise to a number of new translations. The reasons for the updating and producing of new translations are necessitated by the manuscript discoveries, the changes within the English language, and the advancement of linguistics since 1611. Not, as some might assume, because of any faults in the Biblical texts. Today, when someone opens any English Bible (KJV, NASB, NIV, ESV, TNIV, HCSB) they may know that generations of faithful scholarship has managed to preserve and protect that Bible as it was originally given.

Alan S. Bandy, Ph.D. serves as the Rowena R. Strickland Assistant Professor of New Testament & Greek at Oklahoma Baptist University.