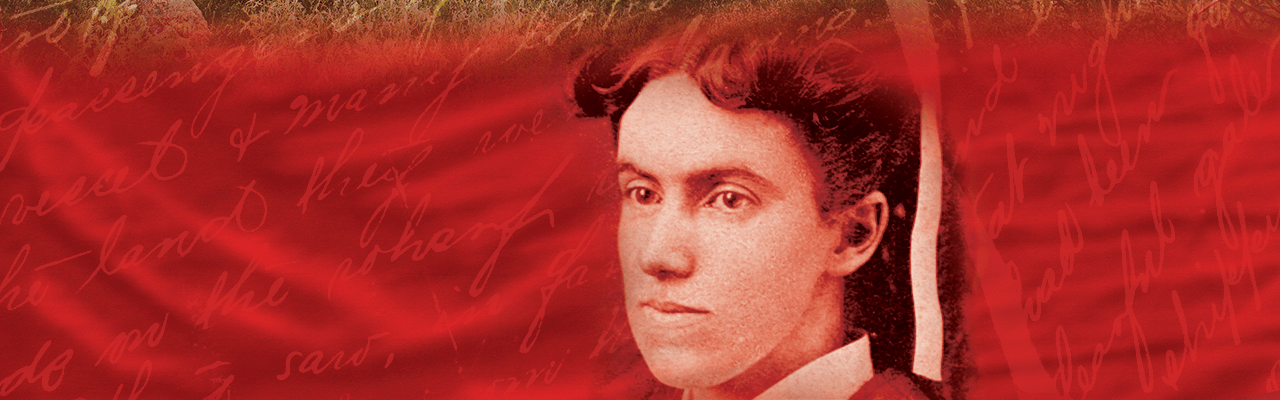

Home for the summer from teaching in Danville, Ky., 30-year-old Lottie Moon shared her interest in missions with her sister Edmonia.

[Photo provided]

One hundred years ago, in 1918, the name Lottie Moon was affixed to Southern Baptists’ annual Christmas offering for missions. It had been Lottie herself who first suggested a Christmas offering—31 years before—in a letter she wrote from China where she spent four decades as a single woman devoting her life to the spread of the Gospel.

Lottie Moon not only established several Gospel-centered schools in China, but she also entered thousands and thousands of homes in China as “the heavenly book visitor”—sharing with hungry hearts the Bread of Heaven, Jesus Christ.

Early life and conversion

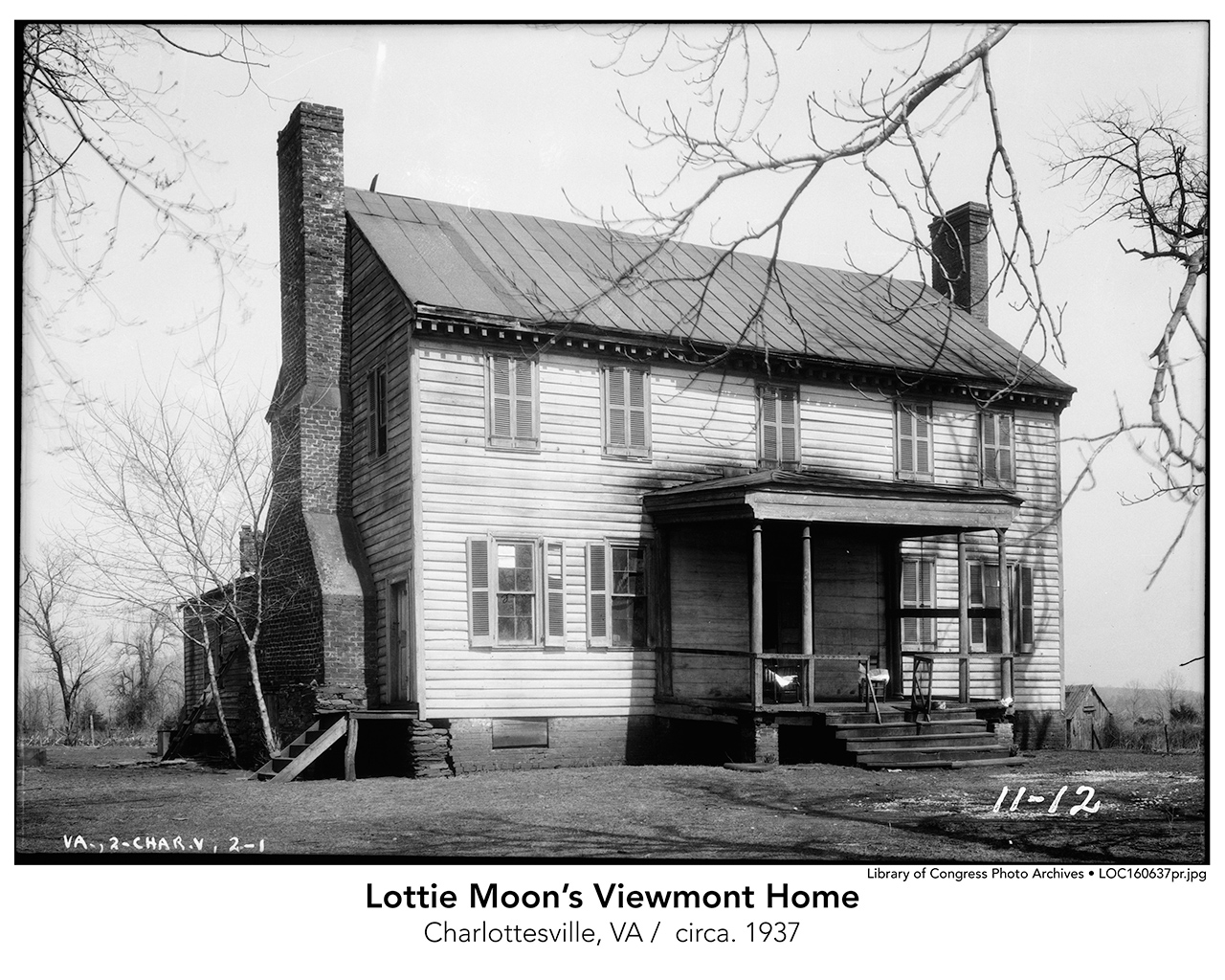

Charlotte “Lottie” Diggs Moon was born on December 12, 1840, in Albemarle County, Va. Her family owned large tracts of farming land and was quite wealthy in the pre-Civil War South. She was the fourth of seven siblings that survived into adulthood. The wealth of the Moon family provided the children, including the girls, with extensive educational opportunities.

Lottie excelled in literature and languages; she learned Greek, Latin, Italian, French and Spanish in school. By the time she completed her master’s degree, well-known Baptist preacher and professor John Broadus considered her to be the “best educated woman in the South.”

Brilliance and education, however, do not equal salvation. In fact, during most of her teenage years, Lottie was becoming a confirmed skeptic of Christianity. Her good grades in school did not include her deportment. She was a prankster who told fellow students that her middle initial “D” stood for “Devil.” Her attendance at school chapel services and Sunday church services became less and less frequent.

In late 1858, Pastor Broadus held a series of evangelistic meetings directed toward students. Lottie’s friends put her on their prayer list for salvation. Lottie surprised them by showing up at their sunrise prayer meeting. She related how a barking dog had kept her from sleeping during the night, and she spent the hours thinking of her soul’s condition before God. She conferred with Pastor Broadus, attended the revival services and was so convicted that she prayed all night.

On Dec. 21, 1858, she told the congregation that she had placed her faith in Jesus Christ and requested baptism, which was administered the next day. Lottie arose from those waters a different woman. Her life and her abilities were now in the hands of her Creator and Redeemer for his use and for His purposes.

Lottie’s journey to the mission field

A 15-year period lapsed before Lottie sensed that God was leading her to missions. The Civil War erupted soon after she graduated, and it changed the face of the South forever. When the war ended, her family’s fortune was completely gone.

Lottie Moon’s home in Charlottesville, Va. c.1937.

[Photo provided]

Lottie set out on a path to teach girls during the early years of reconstruction in the South. Her teaching career led her first to Danville, Ky., and then to Cartersville, Ga., where she started an academy for girls. Her interest in China grew as she began to give financial support to a girl’s school run by Martha Crawford, a Southern Baptist missionary in Northern China.

The unexpected happened when Lottie’s beloved sister, Edmonia, who was 11 years younger, was approved to go as a single missionary to North China. This marked a watershed change in Foreign Mission Board (now International Mission Board) policy. Edmonia wrote to Lottie urging her to join her. “I cannot convince myself that it is the will of Heaven that you shall not come,” Edmonia wrote. “True, you are doing a noble work at home, but are there not some who could fill your place? I don’t know anyone who could fill the place offered you here.”

Her sister’s appeal was followed by a sermon preached by Lottie’s pastor at the Cartersville Baptist Church. His text was John 4:35, “Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest” (KJV). When the sermon ended, Lottie left her front pew. She went to her room where she prayed all afternoon, and it was settled. God’s call to China was “as clear as a bell.”

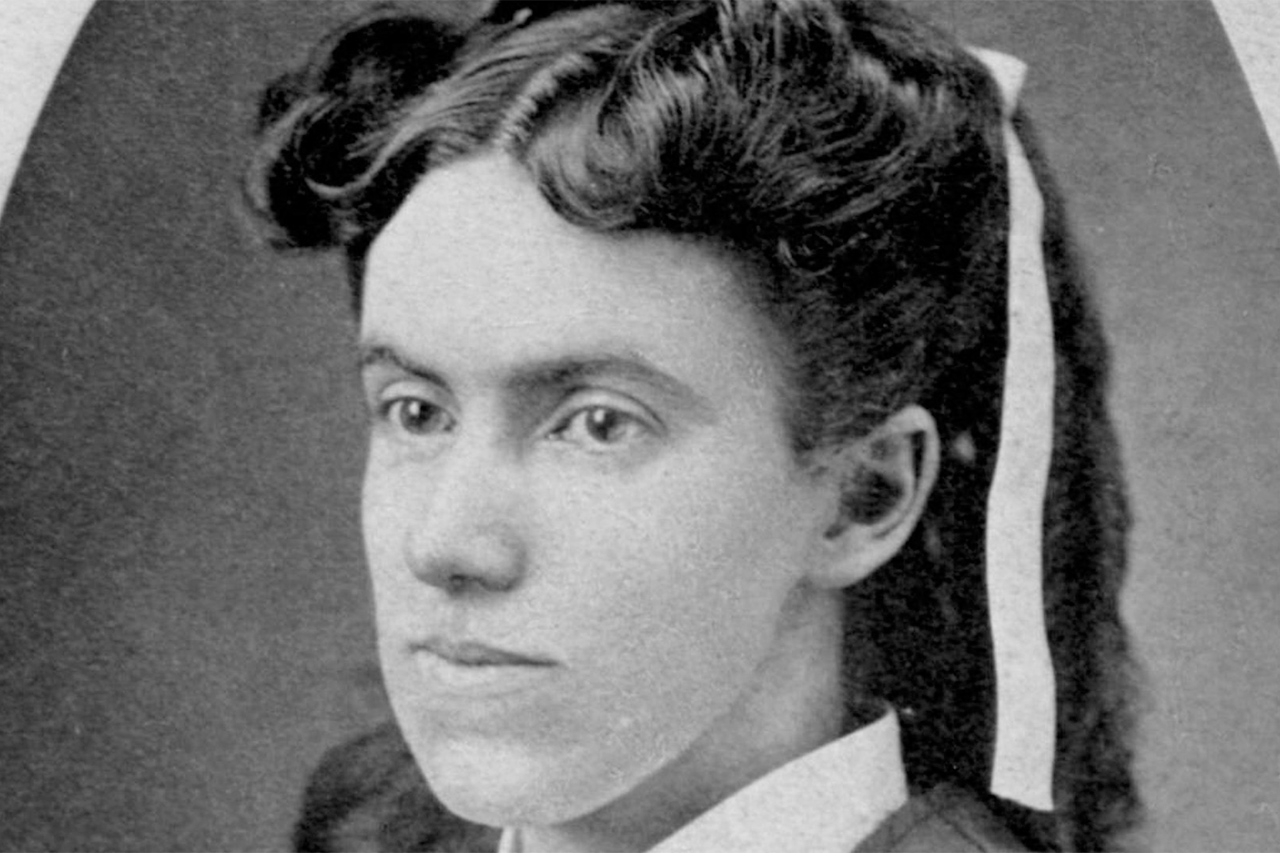

Lottie applied and was quickly approved for missionary service in north China. She immediately turned her hand to one of the most important tasks that would mark the entirety of her ministry. She mobilized churches and Christians by writing letters and articles that promoted missions.

Even before she left for China, she wrote, “Young brethren, can you, knowing the loud call for laborers in the foreign fields, settle down with your home pastorates? So many could be found to fill your places at home; so few volunteer for the foreign work. For women, too, foreign missions open a sphere of labor and furnish opportunities for good which angels might almost envy.”

Lottie continued that practice of using her gift of words to mobilize, saying, “Write. Write at least a half-hour each day. Write constantly to America of the need of these dear people for Christ.”

Ministry in China

Lottie left for China on Sept. 1, 1873. After facing many obstacles, she made her way to the Northern Province of Shandong—the birthplace and final resting place of China’s most influential religious and philosophical leader, Confucius. The city of Tengchow (current-day Penglai) would be her home base for the rest of her life.

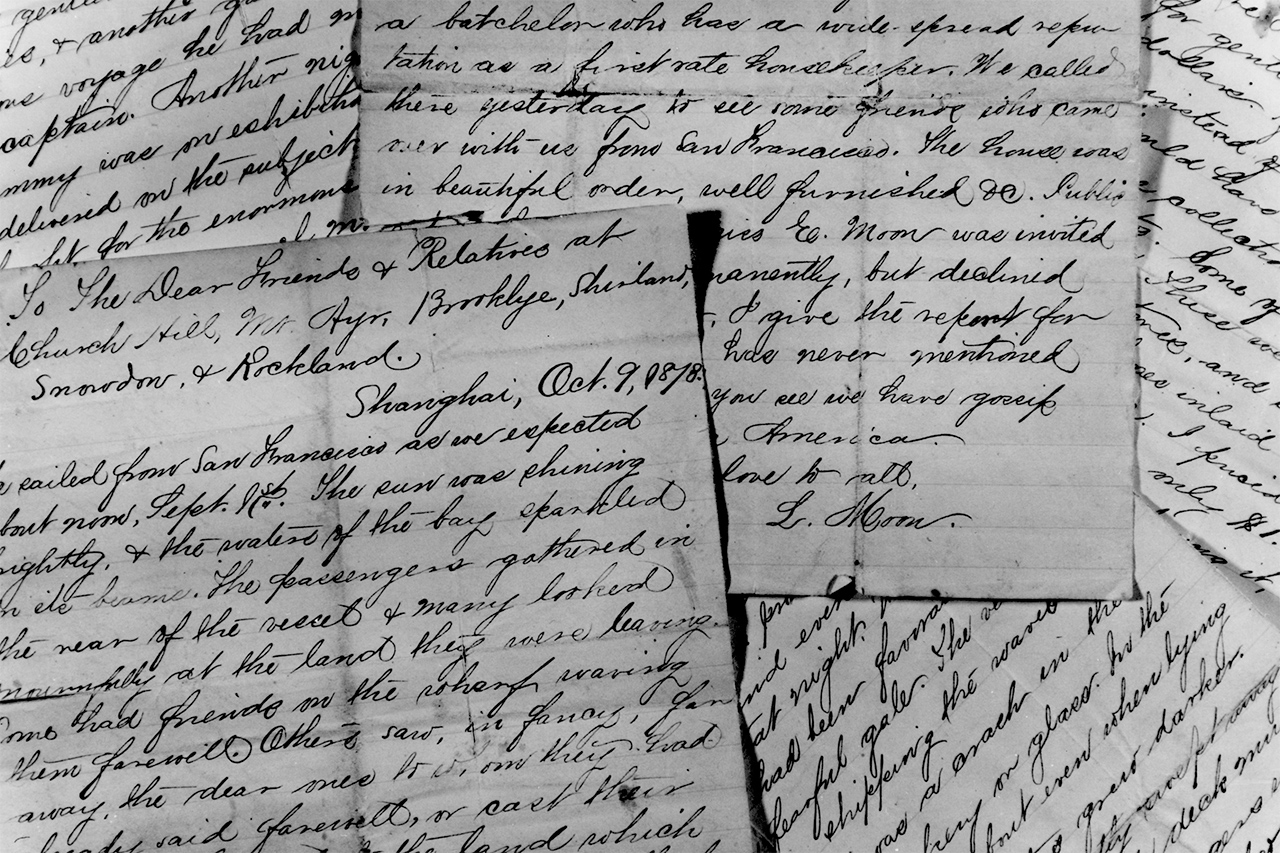

Lottie Moon wrote letters asking Southern Baptists to send more support for missionaries overseas.

[Photo provided]

It was a densely populated region that previously had little contact with the outside world. Thirteen years earlier, Landrum and Sallie Holmes had begun Southern Baptist work in Shandong. Landrum was killed trying to protect the inhabitants from invading rebels. His blood was not shed in vain; people began to listen to the Gospel because of his great sacrifice on their behalf.

Sallie Holmes had remained in Shandong as a single missionary. She and Martha Crawford welcomed the 33-year-old Lottie into their missionary family. Lottie’s initial reception by the Chinese was less than welcoming. She and the others were called “foreign devils.” When Lottie had learned enough Chinese, she retorted, “If I am a devil, what are you? We are all from the first great ancestor.”

They poked and prodded her, asking if she were a man. When she said no, they asked why she was not married. Lottie replied, “Mothers-in-law are too hard to get along with. I’m afraid they will beat me.’’ That answer always broke the cultural ice with great laughter.

First, Lottie applied herself to learning Chinese and then to teaching at a girls’ school. Her heart could not rest in teaching a few dozen girls while surrounded by millions of women and children who had never heard the Gospel.

She found her true calling when she was invited by Sallie Holmes to accompany her on a country picnic, which was really an evangelistic trip to surrounding villages to share the Gospel with anyone who would listen. Lottie said, “The needs of these people press upon my soul, and I cannot be silent. It is grievous to think of these human souls going down to death without even one opportunity of hearing the name of Jesus.”

As a single woman on the mission field in the 1800s, life was difficult, to put it mildly. When she was asked if she had ever been in love, she said, “Yes, but God had first claim on my life, and since the two conflicted, there could be no question about the result.” Lottie’s decisive stand did not free her from the inevitable result: loneliness. Lottie later lamented, “I hope no missionary will ever be as lonely as I have been.”

In 1885, Lottie became the first female Southern Baptist missionary to open a new mission station. This station was in the interior region of Shandong around the city of P’ingtu. In time, this would become one of the strongest missions in all of China.

She also gave herself to training new missionaries upon their arrival. Once she was asked by a group of missionaries why her translation was a bit different than the one they were using. Lottie showed them her Bible. She was reading and translating directly from the Greek New Testament.

By 1912, Lottie was 72 years old, and her health was in very serious decline. Her physical and mental health had been broken by overwork and the pressing needs of the famine-stricken people of Shandong. She gave almost all of her money and food to the Chinese, and she had even stopped eating.

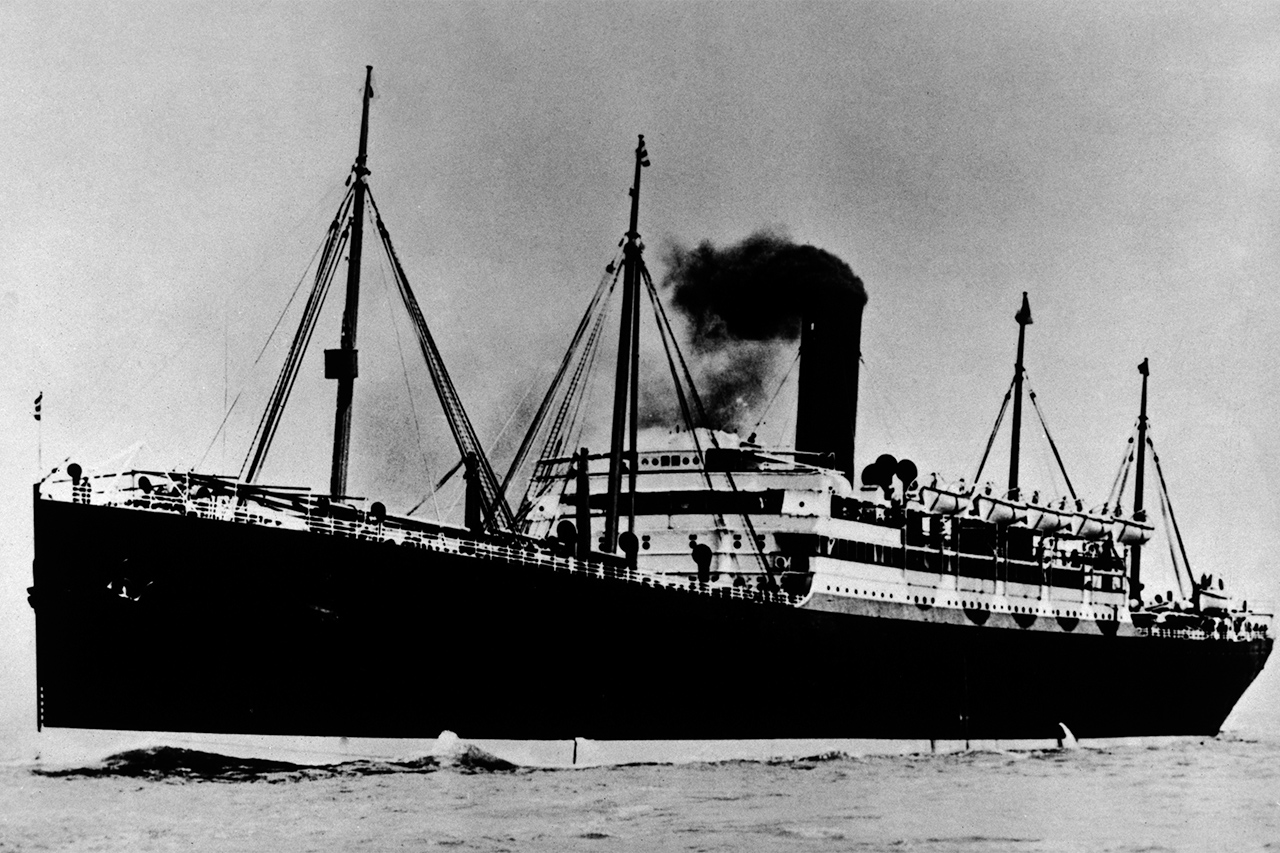

At the turn of the last century, China’s people were starving due to flood, famine and war. Unable to help, Lottie Moon also stopped eating. At just 50 pounds, she died Dec. 24, 1912, aboard the Manchuria.

[Photo provided]

She loved the Chinese, and they loved her. But one of the missionary doctors decided Lottie must return to America to regain her health.

Sadly, Lottie Moon never made it to America. She died in the harbor of Kobe, Japan, on Dec. 24, 1912.

In her final hours, she sang “Jesus Loves Me” with the missionary nurse who accompanied her. Lottie made one final gesture, pushing her fists together in the form of the Chinese greeting. She was welcoming some unseen guest.

On Christmas Eve, Lottie Moon passed into the presence of the Savior who loved her and whose name she had made known. She had fully given her life to Christ and to the spread of His Gospel. Her life is an example that inspires us to live for what truly matters.

David J. Brady is the pastor of Mount Airy, N.C., Christ Community. He was born in Guyana and raised in Belize, where his parents served as Southern Baptist missionaries. David is the author of Not Forgotten: Inspiring Missionary Pioneers, highlighting the lives and labors of eighteen Southern Baptist missionaries. He has also authored an evangelistic book titled The Gospel for Pet Lovers.