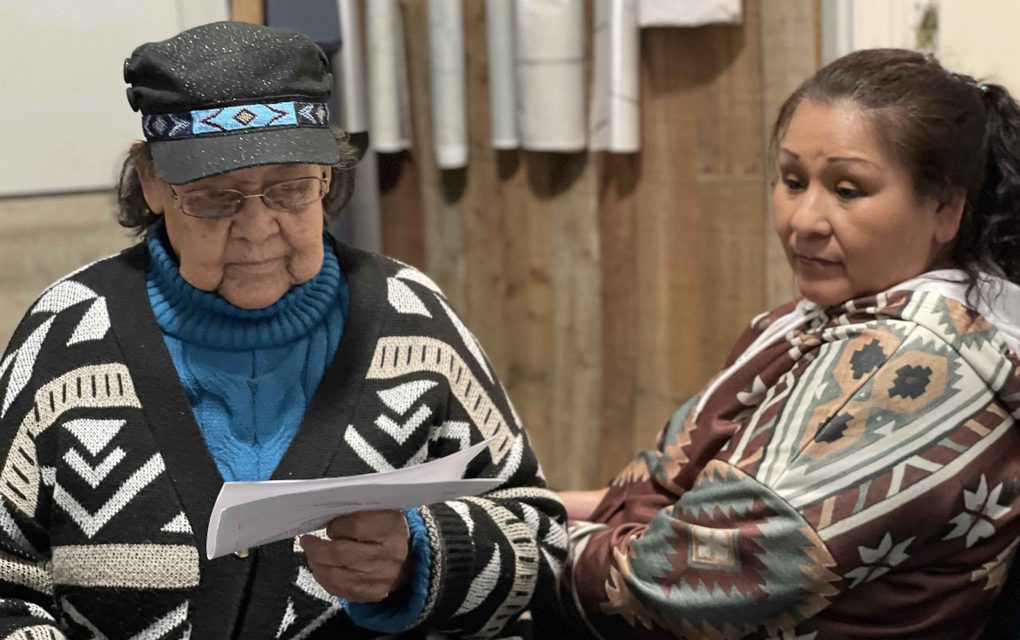

Above: Mary Emarthle, left, coaches a voice actor on the set of “The Savior: A Mvskoke Easter.”

SEMINOLE (BP) – Mary Emarthle, an Oklahoma Seminole Creek grandmother, became enamored in her childhood with the similarity between English and Muscogee when her mother read Scripture to her in their native tongue.

Her father had always told her never to stop speaking Muscogee, rendered “Mvskoke,” and she had spoken it exclusively until she entered first grade in Seminole County public schools, where she was required to speak English.

“I began to look at the (Mvskoke) Bible and compared that with the English, and I was noticing that the vowels and the consonants were the same,” she said. “I would listen to her, and I would look at the Bible, the words, and it began to make sense.

“Like Jesus. In our Mvskoke Bible it’s spelled Cesvs, and that’s Jesus. The C has a G sound. And, of course, the e has the e sound, but the v has the uh sound … Jesus. And I thought, hey I’m gonna try that. And so every time I had a chance, I would look at that Mvskoke Bible and write it out and sound out my vowels.”

Emarthle is using her love and expertise of her native tongue in a collaborative project to translate “The Savior” film into Mvskoke. For her part, she coaches voice actors in speaking the lines added to the original film.

The project fulfills the dream of the late Pastor Bill Barnett, who wanted to see the film translated into Mvskoke as a way of sharing the Gospel with fellow Native Americans.

Hearing the film in Mvskoke will help native speakers, including the Mvskoke Creek and Seminole nations, embrace the Gospel, project collaborators believe.

“He really wanted the people to understand being saved,” she said of Barnett, who died in 2021. “He said, ‘I just don’t feel like they’re understanding. When you’re saved,’ he said, ‘you continue to believe in the Lord.’ … He said, ‘I think they really need to understand commitment. I want them to understand that Jesus is coming back someday.’ And then he said, ‘and when He calls them, I want them to be ready.’ … I agreed with him.”

Emarthle is working with a team including Barnett’s daughter Jennifer Barnett, the project’s culture and language coordinator, and director Aaron Hanzel.

Jennifer Barnett, the minister of education at Seminole, Indian Nations, planted by her father in 1975, is of Mvskoke and Cherokee heritage.

“I didn’t grow up fluent in (Mvskoke) by any means,” Barnett said. “And so this has just been an opportunity too to help carry that on, that desire of theirs to preserve that language, but ultimately really to have this as a tool to also share the Gospel to their own people.

“I wanted to see the vision of my father and these other people, and to also want to learn more Mvskoke,” she told Baptist Press. “I grew up hearing my father speaking Mvskoke with his siblings and other people.” As Barnett’s mother is Cherokee, a language quite different from Mvskoke, the Barnetts spoke English in the home.

Barnett was born into the Southern Baptist family, is a baptized believer and has attended Native congregations her entire life.

“I know that God has called me to serve among Native people, not just Mvskoke and Cherokee people, but to encourage and want to build up other Native believers to grow in their faith and their service to the Lord,” she said. “And so I see that as an extension to this.”

She relates it to the apostle Paul’s “God-given” desire to see the Israelites saved, even as he fulfilled his mission to the Gentiles.

The scenes from The Savior relating to the resurrection are already completed and available for free download as “The Savior: A Mvskoke Easter” in a variety of formats with or without subtitles. Designed as an opportunity to share the Gospel in Mvskoke at Easter, the resurrection release is the second release in the project aimed at translating the entire Savior film into Mvskoke. “The Savior: A Mvskoke Nativity,” was released at Christmas. Project collaborators hope to translate the entire film, assembling a team of about 70 people.

Emerson Falls, Native American ministry partner with Oklahoma Baptists, served as a consultant in the early phases of the project. He sees benefits culturally and spiritually.

“It’s very important to the tribes for language preservation. It helps the people to hear it. It helps the people to speak it,” Falls said. “The second thing is, for us as Christian people, it’s a way for us to connect with the larger unchurched Native American audience. As this gets shown in our tribal communities and other places … we believe that they’ll hear the Gospel. And so we think this is important to combine the two.”

The project also spreads the fact that Native languages are dying, Falls said.

Native languages have been declining for decades, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Native Americans. Already, 65 languages are extinct and 75 are nearing extinction, with 245 indigenous languages remaining in the U.S., HHS said, based on an analysis of data from Ethnologue.

“Assimilation is causing the loss of our languages,” Falls said. “All of the tribes really are working very hard to preserve our language and to teach it to a new generation. This is something that’s important to the tribes. Language preservation is a priority.”

Hanzel, who is Chickasaw and Choctaw, learned of the project through the Skit Guys’ director Brian Cates. Hanzel described Cates and Behold Pictures, the Skit Guys’ production company, as essential to keeping the project afloat.

“It’s a lot of fun to be able to help preserve the Native language in both the oral and the written form,” Hanzel said. “We get to help preserve the Mvskoke language in the dubbing sessions and there are subtitles in the video as well. So you get to hear and see exactly how Mvskoke was intended to be.

“Very rarely do you have a project like this where you get to preserve the language, then get to share the Gospel,” Hanzel said. “The language and the people group exist because God created it. To me, that’s a beautiful thing to preserve a language for a people group that is so small. We have multiple generations helping with this project.”

Hanzel grew up in the U.S. and Central Asia with parents who were International Mission Board missionaries. His mother is Native American, and he grew up immersed in the culture.

“Native culture is so a part of my life,” he said, “and I think my hope and desire for this project, for people that aren’t Native American, is they get to experience some of me. They get to experience some of my family. They get to experience other tribes that have different but similar aspects to it of the pride, the joys and the stories.”

He finds beauty in the Native languages.

“The language is familial. It feels like family,” he said. “You can tell it’s ancient. You can tell it’s been around a long time, and that’s always cool to me, because with that in mind, it carries with it generations of people, and it carries with it generations of experience, generations of stories, generations of a common bond.”

Emarthle expresses a passion to return the spoken language to its original beauty and cadence.

“Preserving the language keeps the people together,” Emarthle said. “It’s just funny the way, when we talk in our language, we say comical things. And we try to say it in English, and it doesn’t come out like that. It’s important that we keep our language going.”

While the Mvskoke word for Jesus – Cesvs – is similar to the written English, the word for God is not.

In Mvskoke, Emarthle said, God is written Hesaketvmese, translating literally to breath of life from God.

Emarthle often has to correct the pronunciation of the language on the set.

“I always call it English-flavored language. They want to kind of abbreviate it and kind of make it sound more like English than the Native language. They don’t stress the dialect the way we’d like for them to. It’s kind of amusing sometimes.”