NASHVILLE, Tenn. (BP)—Four hundred years after the Mayflower landed in Plymouth Bay, the Pilgrims’ legacy has fallen on hard times.

Contrary to the traditional portrayal of Pilgrim families gathered around their tables with heads bowed in prayer, some historians question whether deep Christian faith should be associated with the Mayflower Pilgrims and their first Thanksgiving. The New York Times’ 1619 Project claims the Pilgrim story is among American history that needs reframing in light of “anti-black racism” already “in the very DNA of this country” when the Mayflower reached the New World.

Not so fast, say evangelical Pilgrim scholars Richard Land and Michael Haykin, who assert that the settlers who arrived at Plymouth were neither irreligious nor enslavers. Their vision for America was among the purest tributaries to feed U.S. democracy and helps confront contemporary challenges to freedom—from the sexual revolution to unreasonable pandemic-era restrictions on worship.

Pilgrim principles were “the ground out of which the Declaration of Independence grew,” said Land, president of Southern Evangelical Seminary and former head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission. The Pilgrim colony’s governing document, the Mayflower Compact, is “the American Magna Carta.”

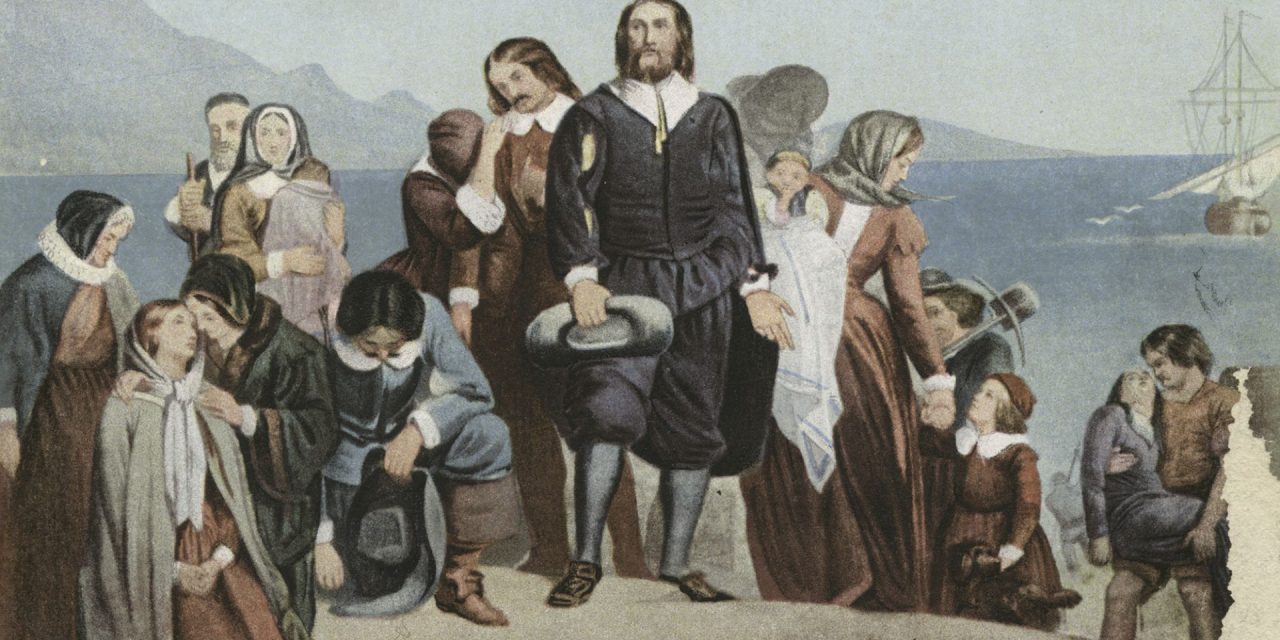

After an 11-week voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, 102 Mayflower passengers reached Cape Cod, Mass., Nov. 21, 1620 (Nov. 11 on the older Julian calendar utilized by the Pilgrims). About 40 of them were from a religious group known as Separatists—Christians who had separated from the Church of England because they rejected the notion of a state church in favor of a church comprising only born-again believers in Christ. They had fled religious persecution in England, settling first in the Netherlands before making the journey to America in search of continued religious freedom, better economic prospects and removal from the influence of poor Dutch morals on their children.

The rest of the Mayflower passengers, known as “strangers,” focused on economic prospects in the New World, not sharing the Separatists’ deep commitment to Christ.

The Separatists and strangers intended to land the Mayflower farther south, in present-day New York. But having veered off course, they found themselves outside the area where the king of England had granted permission to settle. To maintain order while waiting for new permission, the adult male settlers signed the Mayflower Compact.

They covenanted together to form a “civil body politic” that became known as Plymouth Colony to “frame such just and equal laws” as “shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony,” according to the Mayflower Compact. It was democracy by consent of the governed, a religious people with a secular government, a free church in a free state.

The democratic experiment worked. Despite a brutal first winter in America and a mediocre harvest, the Pilgrims celebrated the first Thanksgiving in the fall of 1621 to thank God for His providential care over their colony.

Plymouth Colony disappeared by 1691, absorbed into Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony to its north. Yet Plymouth’s legacy lived on. It has been cited since the Revolutionary period as a foundational part of the American story.

In recent years, however, its foundational status has come into question – along with the notion the first Thanksgiving was a deeply spiritual occasion.

Historians James Deetz and Patricia Scott Deetz claimed, for example, “Thanksgiving as we think of it today is largely a myth.” The original celebration was a “secular event,” which “transformed over time” because America “needed a myth of epic proportion on which to found its history.”

The Times’ 1619 Project—originally published in 2019 and named for the year the first slaves arrived in North America, was controversial and prompted pushback from some historians. It claims America’s racist course was set a year before the Mayflower set sail, and “our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written.” The Pilgrims did not change that reality, according to The Times.

Such revisionist notions misrepresent the Pilgrims and their significance, said Haykin, co-editor of “Strangers and Pilgrims on Earth: Remembering the Mayflower Pilgrims, 1620-2020.” The Pilgrims did not own slaves, he said, and they were deeply committed Christians who helped establish “religious liberty as a concept in Western culture.”

Philosopher John Locke, “one of the great architects of the concept of religious toleration,” studied church-state relations in the English Puritan and Separatist tradition, said Haykin, a church history professor at Southern Seminary. The Founding Fathers then drew from Locke as they crafted the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

“It really (was) quite radical” in the Pilgrims’ day “to believe that the state should allow individuals to worship according to their conscience,” Haykin said. “Virtually nobody believed that in Western Europe.”

But that minority view prevailed in America, spawned in part by the Pilgrims.

“The Founding Fathers were very educated,” said Land, who studied historical theology at Oxford under English Separatist scholar B.R. White. “They studied the Pilgrims.”

In addition to religious liberty, Land said, the Mayflower Compact articulated other early principles of American democracy, including the notion of a religious people living under a secular government. By the American Revolution, the story of Plymouth was widely known and Pilgrim descendants fought in the Continental Army. Four score and seven years later, Abraham Lincoln seemed to draw from the Pilgrim tradition in the Gettysburg Address when he referenced a “government of the people, by the people (and) for the people.”

“Lincoln understood the Pilgrims in his bone marrow” because they were part of every 19th-century American education, Land said. “The Gettysburg Address came from that.”

Pilgrim ideals remain relevant in the 21st century, he said, as some U.S politicians seem to ignore the need for consent of the governed. When governors unilaterally restrict the size of family Thanksgiving gatherings or worship gatherings, “the Pilgrims would say, ‘Wait a minute. Let’s vote on that.’”

The Pilgrim tradition also stands against government attempts at restricting Christians’ right to oppose homosexuality and transgenderism, according to Haykin.

“The issue is quite different from what the Pilgrims faced,” he said, but “the principle is still the same: the state has no right to dictate to the church various aspects of her belief.”

Eventually, the Pilgrims’ descendants in Massachusetts Bay both participated in the slave trade and diluted their commitment to religious liberty (as when they exiled Roger Williams, founder of the first Baptist church in America). Their sad failure to live out Plymouth’s ideals in the long term “is a recognition of the weakness of humanity,” Haykin said, and has fueled Pilgrim critics.

Nonetheless, the Mayflower voyage and original Pilgrim settlement remain “one of the great turning points in Christianity.”