LOUISVILLE, Ky. (BP) — “Stay in the story.” That’s the advice retiring missionaries Nik and Ruth Ripken offer the next generation.

“Don’t quit before you see all that God has for you,” Ruth said. “Don’t get sidetracked.”

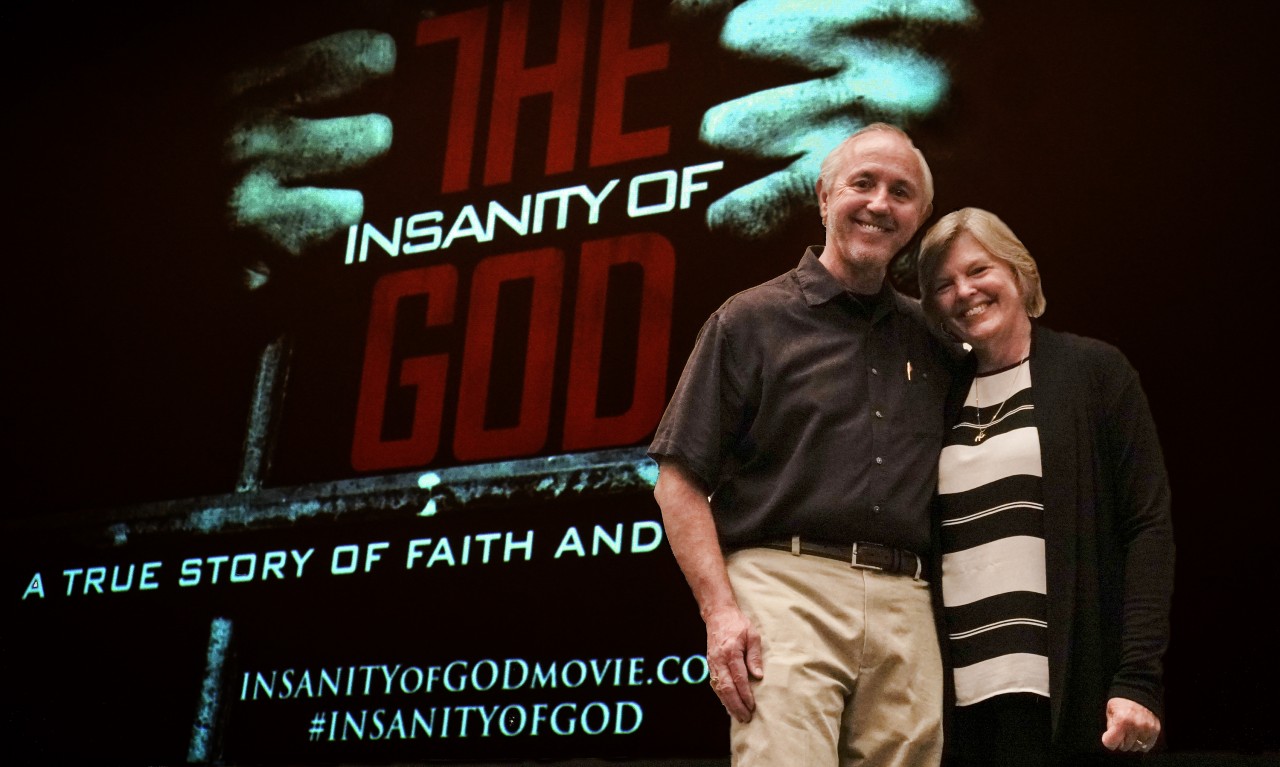

The 2016 film “The Insanity of God” told the story of missionary Nik and Ruth Ripken’s ministry among persecuted believers. BP file photo

The Ripkens, known for their extensive research into Christian persecution, have relocated to Louisville, Ky., having signaled their retirement for March 2020 after 35 years of service with the Southern Baptist International Mission Board.

Originally from Kentucky, the Ripkens were appointed by the then-Foreign Mission Board in August 1983. Through the course of their career, they lived in seven countries: Malawi, South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, Germany, Ethiopia and Jordan. With a recent trip to Cuba, the list of countries they’ve visited reached 86.

“We’ve also sat with believers in persecution for days and days at a time in 72 of those countries,” Nik said.

Those in-depth conversations shaped the Ripkens’ lives and legacies. Their research, which spanned 15 years, resulted in hundreds of interviews and culminated in two books, “The Insanity of God” and “The Insanity of Obedience,” and the feature film, “The Insanity of God.” More than 90,000 people in 800 theaters viewed “The Insanity of God” when it was released in August and September 2016.

Easter Sunday 1997

For the past several years, the Ripkens have focused on sharing in small groups, churches and conferences the insights they gained as they talked with persecuted believers across the globe.

Their quest for understanding began after the death of their son Timothy in Nairobi, Kenya, on Easter Sunday 1997. Timothy died at age 16 from cardiac arrest brought on by an asthma attack.

Describing the day of Timothy’s death in “The Insanity of God,” Nik wrote, “I was overwhelmed by my own loss. Ruth used the word ‘resurrection’ that night; I was fixed on the crucifixion. The pain was unbearable.”

Ruth felt Timothy’s death was the most challenging experience of her missionary career, and the challenge of moving past the grief was equally great.

“Beyond [Timothy’s death] was figuring out how I continue to serve and live and be who I need to be post that,” Ruth said.

“How do I carry on? Believers in persecution taught us how to do that.”

The key, she said, is to “stay in the story.”

Yearly letters

Nik and Ruth’s story began in rural Kentucky. As a 9-year-old girl, Ruth attended Camp Cedarmore in Bagdad, Ky. There she met Bertha Smith, a Southern Baptist missionary who served in China and Taiwan from 1917 until her mandatory retirement at age 70 in 1958.

“I felt so overwhelmed by the Holy Spirit that that’s what I wanted to do,” Ruth said. She talked with a few people about what to do next, and they told her to write the Foreign Mission Board.

“I did, and they sent back information,” Ruth recounted. The mission board encouraged her to write every year and tell them where she was in the process.

When the Ripkens went for their appointment interview with the FMB in 1983, the consultant showed the Ripkens their files. Ruth’s file contained every letter she had written the FMB since she was 9 years old.

“She had a small book,” Nik said, “and I had a page.”

Throughout their career, the support of believers helped the Ripkens stay in their story. Ruth recalled the number of people across Kentucky and elsewhere who wrote them when they were serving overseas.

“As we went to Malawi and East Africa and South Africa, ladies all over Kentucky handwrote letters to us, encouraging us in our journey,” Ruth said. “Over the years, we could see their handwriting disintegrate (as they began to age)…. So many women invested a lot of time in supporting those who were going to the nations.”

Then, after Timothy’s death in 1997, Nik and Ruth lived on the campus of Georgetown College in Georgetown, Ky., from 1997 to 2000, hosting 60 to 90 students in their home for six hours every week. Of those, 60 have served as short- or long-term missionaries, Nik said.

“Those students loved on us during that time,” Ruth said. “Many of them are now overseas. We feel a huge responsibility to be a foundation and support to them as people have been to us.”

‘Stay in the story’

Understanding the long view of God’s plan helps believers stay in the story. In many cases, this may mean enduring difficult situations much longer than we think possible or necessary, Nik said.

One powerful scene in The Insanity of God is the story of Dmitri, the pastor of a small house church in the former Soviet Union. One night, communist officials burst into his home during worship. They arrested Dmitri and sent him to prison for 17 years, more than 600 miles from his family.

Dmitri was the only believer among 1,500 hardened criminals. The isolation from the body of Christ combined with the physical torture tested his faith and strength. But he found a way to endure.

“For 17 years in prison, every morning at daybreak, Dmitri would stand at attention by his bed,” Nik wrote. “As was his custom, he would face the east, raise his arms in praise to God, and then he would sing … to Jesus…. The other prisoners banged metal cups against the iron bars in angry protest. They threw food and sometimes human waste to try to shut him up.”

Then, one day, after finding a piece of paper on which Dmitri had written every Scripture reference, Bible verse, story and song he could recall, his jailers beat him severely and threatened him with execution. As they dragged him from his cell down the center corridor toward the courtyard, Dmitri heard a strange sound.

The 1,500 criminals who had long ridiculed him stood at attention by their beds. They faced the east, raised their arms and began to sing the song they had heard Dmitri sing to Jesus every morning.

“Who are you?” a guard demanded.

“I am a son of the living God, and Jesus is His name!” Dmitri replied.

The guards returned Dmitri to his cell. Sometime later, he was released and told Nik his story.

About six months ago, Nik heard that Dmitri had died. Nik contacted his son, who assured him Dmitri was still alive.

“He is hurting every day from the abuse he endured, but he wakes up every day singing with joy. He is living a life of joy because his story is all over the world,” Dmitri’s son said.

“Dmitri’s story has outlived the persecutors’ stories,” Nik said. “His story has outlived the Soviet Union.”

As Nik started to end the call, the son said, “But Nik, wait. I want to tell you something. I’m now the chaplain at the prison that held my father for 17 years.”

“There is not a single minute, hour or day in those 17 years when Dmitri would have imagined that his son would be the chaplain in that prison,” Nik said. “But look what God can do when you stay in the story.”