This article was originally written by Diana Chandler and published to BaptistPress.com. Feature image courtesy of The First Hymn Project.

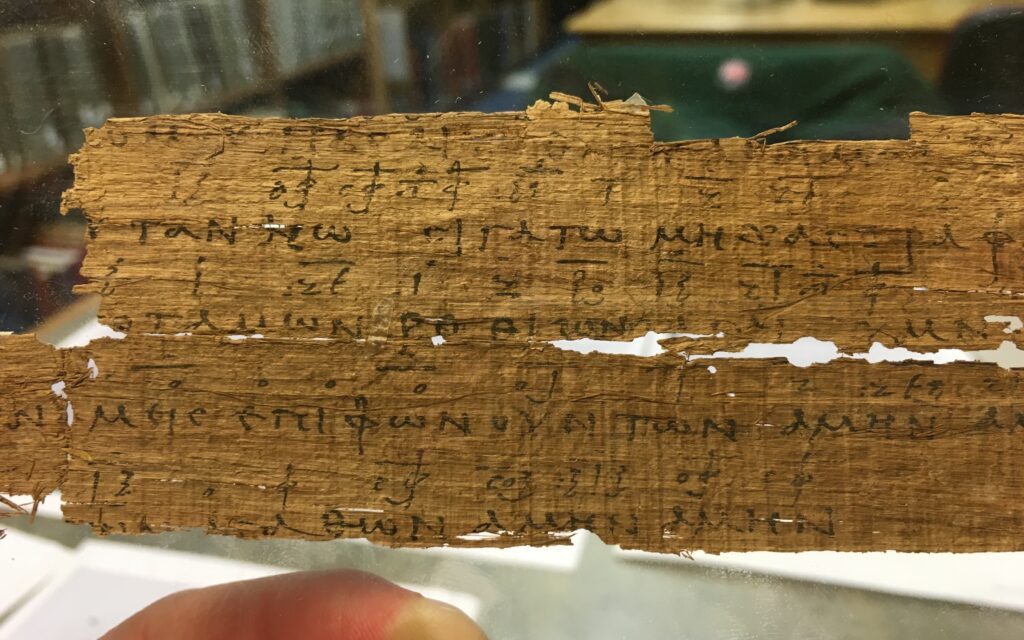

LA MIRADA, Calif. (BP) – What was left of the hymn, archeologists found 100 years ago in ancient Egyptian ruins on a scrap of tattered papyrus, long buried by desert sand. The discovery was sealed in a climate-controlled vault at Oxford University until John Dickson came along.

Dickson, who joined Wheaton College in 2022 as the inaugural Jean Kvamme Distinguished Professor of Biblical Studies and Public Christianity, began to realize the importance of the papyrus for today’s Christians.

“I’m thinking, why has no one brought this back to life? You know, this is a song from before there were denominations,” he told Baptist Press. “And it’s thoroughly Orthodox Christian theology.”

Chris Tomlin, Ben Fielding, and John Dickson collaborated to resurrect The First Hymn, the earliest known Christian hymn. The First Hymn Project photo

Archeological dating could certify without a doubt, Dickson said, that the hymn dated to the mid-200s, owing to paleography and “a corn contract on the back” of the papyrus. About a fifth of the words, the beginning lines, were missing, he said, as well as the corresponding tune to the missing lyrics. But the rest, including a tune that would have resonated with pagans of the day, was intact.

What is most notable, Dickson said, is the certainty with which the song presents the Trinity, although it predates by generations the Council of Nicaea, in 325 AD, which scholars say confirmed the Trinity.

“It’s clear evidence that Christians were singing their Trinitarian beliefs from an early period,” Dickson said. “And it’s wonderful that this one example … in the pagan notation style, is all about the Trinity. That’s just remarkable.”

“We need to give this back to the Church,” he concluded.

But Dickson’s challenge was rebirthing the hymn in tune and lyrics for today’s Christians, while maintaining the high praise of the early Christians.

“There’s no way we can give it back to the Church in Greek or in that funny melody,” Dickson reasoned. “So why don’t we try and get some of the greatest songwriters to create a new version of it that uses my translation, all of the original words, and tries to use as much of that original melody as possible … but creates a new song so that everyone can sing it?

His solution? Call in the heavy-hitters, the high praise-ologists and Grammy-winning worship songwriters who have stirred hallelujahs globally. That translated to Chris Tomlin, whom Time Magazine has hailed as “potentially the most often sung artist in the world,” and Ben Fielding of Australia. You might not know his name, but he wrote songs you sing, including “What A Beautiful Name” and “Mighty to Save.” Fielding is the only songwriter to have four songs reach No. 1 on Christian Copyright Licensing International’s most sung songs in the global Church.

The massive collaboration comes together in a song, The First Hymn Project, releasing April 11 worldwide, and the accompanying documentary featuring a cast of scholars streaming April 14 in the U.S. on Wonder. Special documentary showings and concerts are scheduled 7-9 p.m. April 14 at Biola University in La Mirada, Calif., and April 15 from 7-9 p.m. at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C.

For Fielding, he told Baptist Press, the first hymn proved the most rewarding and intriguing projects he had ever encountered.

“I had no idea that such a significant discovery lay quietly in England, fairly certain that most modern-day Christians would, like me, have no awareness of its existence,” Fielding said. “Now we were being tasked with bringing it back to life, that the Church today might be able to sing with (the) very same words our brothers and sisters in Christ were singing 1,800 years ago.”

About 35 words of the original song were available, Dickson said. Translating the Greek, Dickson sees the original lyrics as:

“Let all be silent, the shining stars not sound forth, all rushing rivers be stilled as we sing our hymn to the Father, Son, the Holy Spirit, as all powers cry out in answer, Amen, Amen, might, praise and glory forever to our God, the only giver of all good gifts. Amen. Amen.”

Musicologists transcribed the ancient entity into a modern stave, Fielding said, and the finished recording opens with an Egyptian Coptic Christian singing a bit of the ancient melody.

“However, we knew that for the song to work well in a contemporary church setting,” Fielding said, “we would need to reinterpret the music, in particular, the melody.”

The original melody was a pub song that anyone on the ancient third-century streets could sing, Dickson said, perhaps a tune that would be used to sing to a false god such as Zeus.

“If you’re a believer in Zeus, this is very confronting, partly because the last line of the hymn says to our God the only giver of all good gifts and yet, Zeus was called giver of good gifts,” Dickson said. “These Christians have said, ‘Our Lord is the only giver of all good gifts.’ It seems to be a kind of playing on what pagans said of Zeus, but they’re actually saying not Zeus, but our Lord.”

Fielding was fascinated to see third century Christians embracing Trinitarian theology, and praising God amid persecution.

“Trinitarian theology was alive and well in the church,” he said. “Further, despite the external resistance facing the church in the third century, the persecution and perhaps even doubt as to whether the message and their own lives would survive, they sing – what I think is the pinnacle of the hymn – to ‘the only giver of all good gifts.’

“So great was their confidence in the Lord,” Fielding said. “We can draw great encouragement, that our circumstances don’t determine how praiseworthy Jesus is. God is working all things together for good for those who love Him.”