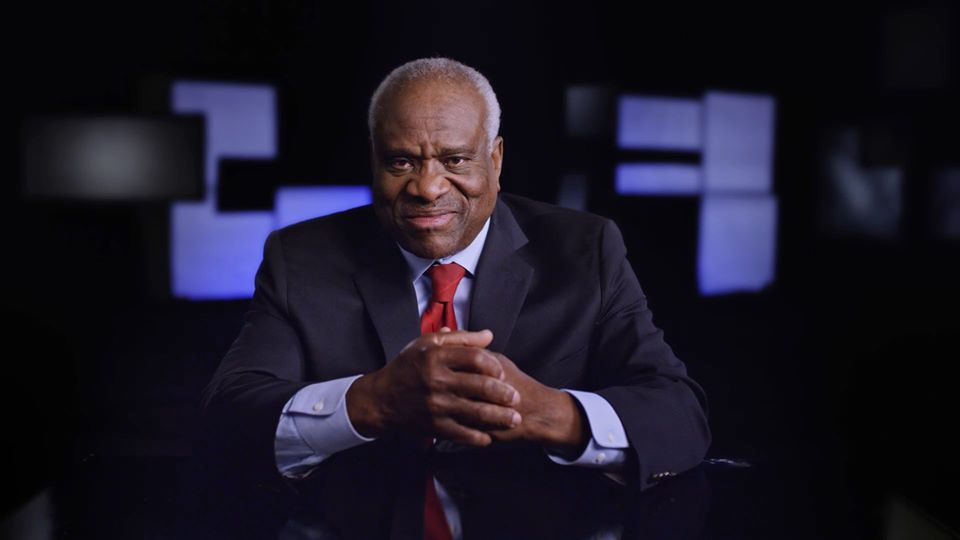

A new documentary, ‘Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words,’ tells the amazing story of Thomas’ life through the voice and eyes of Thomas himself.

He was a self-identified left-wing college radical who wore Army fatigues. He embraced Marxist leaders and took part in a violent protest. And when he graduated from law school in the 1970s, he thought working for a Republican would be “repulsive.”

But somehow, Clarence Thomas grew up to become one of the most conservative justices in the modern history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

A new documentary—Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words (PG-13)—tells the amazing story of Thomas’ life through the voice of Thomas himself. Based on 30-plus hours of interviews with Thomas, it follows this transformative figure, from his childhood, to his college and young adult years, to his unforgettable confirmation battle of 1991.

The film is the inside story of the most “silent” justice in Supreme Court history—he famously never asks questions—and it is as gripping as it is entertaining.

At times, it’s even surprising.

Thomas grew up in the segregated southern city of Savannah, Ga., initially living with his mother in a run-down house where sewage flooded into yards. (It filled the ditches, and they used a plank to walk over the smelly mess.) He then moved in with his middle-class grandmother and grandfather, who sent him to Catholic school. This is where faith was ingrained into Thomas. His grandfather had a “philosophy of life” that came from the Bible, believing the world was fallen because of what happened in the Garden of Eden.

A few months shy of his 16th birthday, Thomas decided he wanted to be a priest. He entered seminary—“I loved the contemplative life”—but was troubled by the racism of a handful of classmates. (One passed him a note in class reading, “I like Martin Luther King … dead.” When news broke of King’s assassination, a classmate exclaimed, “Good.”) The Catholic church, he says, did not take a firm stance on civil rights. So, he dropped out.

His next stop was Holy Cross, which he entered in 1968 during a tumultuous era in U.S. history. Thomas quickly embraced this radicalism by wearing Army fatigues and aligning himself with radical groups and leaders. Yet after he took part in a violent protest on another college campus, he felt guilty. He stopped in front of a chapel and prayed to God, “If you take anger out of my heart, I’ll never hate again.”

Thomas graduated from Yale Law School as a registered Democrat, but his only job offer was working with Republican Missouri Attorney General John Danforth. He considered the idea “repulsive,” but nevertheless took the job. That’s where Thomas’ outlook on life began to transform. In 1979 he took a position as a legislative aide to Danforth, who had been elected to the U.S. Senate. In 1980, Thomas voted for Ronald Reagan, a Republican. He then accepted a position within the Reagan administration. (He was attracted to Reagan’s push to stop the “social engineering” of the 1960s and 70s.)

Thomas’ judicial philosophy was influenced by his study of slavery and segregation in the U.S.—and why a nation founded on equality could have permitted both. He was searching, he says, for a set of legal ideals that said slavery and segregation were wrong. He discovered natural law, which he says was embedded in the Declaration of Independence’s statement that “all Men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.”

“The framers understood natural law and natural rights a certain way, and it is an underpinning of our Declaration, which then becomes a foundation for the Constitution,” Thomas says. “They start with the rights of the individual, and where (do) those rights come from? They come from God. They’re transcendent.”

His personal views about a law, he says, don’t matter.

“When interpreting constitutional text, the goal is to discern the most likely public understanding of a particular provision when it was adopted… A bad policy can be constitutional. A good policy can be unconstitutional. So that’s why we start with a text.”

Thomas’ faith is a major theme in the documentary. During his contentious 1991 confirmation hearing—he was facing allegations of sexual harassment he denied—he and his wife held a Bible study with friends. The subject: Paul’s admonition to wear the “armor of God.” (His wife says of the allegations, “It felt like the demons were loose.”) Minutes before Thomas went before the Senate committee to respond to the allegations, Danforth told him, “Go in the name of the Holy Ghost.” Thomas labeled the committee’s handling of the allegations a “high-tech lynching.” God, he told the senators, “is my judge.”

Thomas also answers those who mock and ridicule him for not aligning himself with positions historically held by black groups. He calls such mocking “stereotypes draped in sanctimony and self-congratulation.”

“If you criticize a black person who is more liberal, then you’re racist,” he says, “whereas you can do whatever to me, or to now Ben Carson, and that’s fine, because, ‘You’re not really black because you’re not doing what we expect black people to do.’”

The Supreme Court often is viewed as mysterious, partially because cameras aren’t allowed in the courtroom. And Thomas—because he rarely speaks during the sessions—perhaps is the most misunderstood member of the court.

Created Equal gives us a fascinating peek into Thomas’ life. Just like other recent films about the justices—RBG and On the Basis of Sex come to mind—it’s worth watching.

Content warnings: The film includes brief footage of Anita Hill’s sexually explicit testimony—footage that earned it a PG-13 rating. Coarse language includes d–n (4), misuse of “G-d (3) and SOB (1). Most of the language involves Thomas quoting someone else.

Rated PG-13 for thematic elements including some sexual references.

Visit JusticeThomasMovie.com for a listing of theaters.

Entertainment rating: 4 out of 5 stars. Family-friendly rating: 3 out of 5 stars.

PHOTO CREDIT: Manifold Productions